I was scrolling on Mastodon yesterday — the ad-free, federated social media I went to after finally leaving Twitter and Facebook for good a few years ago — and came across these two images that I modified.

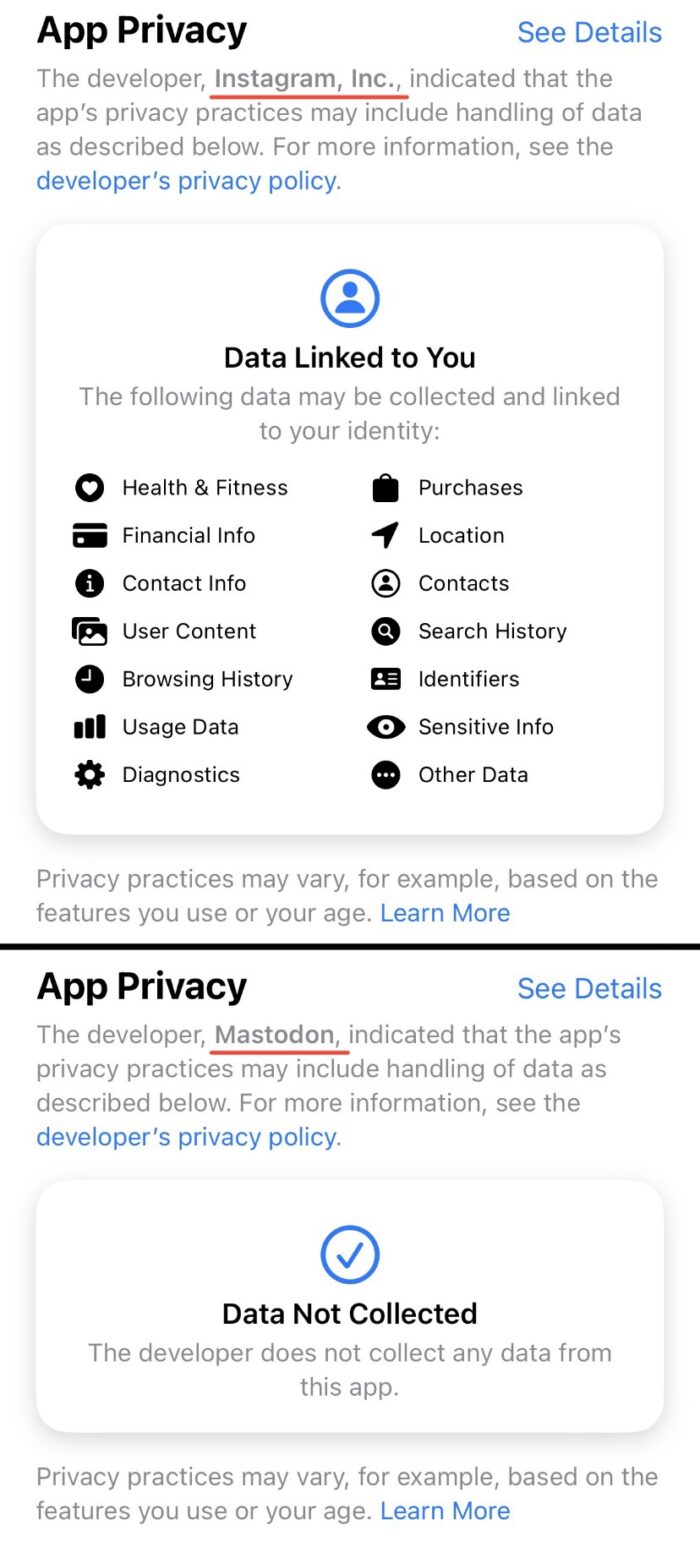

The Apple Store, where Apple devices get their apps, has long had a section deep on their app info breakdown that shows you what information the app collects about you. I took these posted images and merged them into one for a single-look comparison between the two.

What is shows is the types of information that Instagram collects about you (Instagram is owned by Facebook/Meta), compared to what Mastodon collects about you:

What you’re seeing is that Facebook/Instagram basically collects everything it can about you. I literally don’t think there are any other categories available in the Apple App store for developers to collect info from. When creating their app, they simply turned up all data collection knobs to the maximum. Which is a stark difference from Mastodon, which collects absolutely nothing.

A brief explainer for anyone whose head is swimming by all of this: Facebook and Instagram are among the big social media companies that make hundreds of billions of dollars a year selling ads (a quick calculation I ran last year had Facebook earning more per year than all of Canada’s banks combined). The way it makes that money is by having unprecedented volumes of data on every one of its users, which allows it to parcel out extremely detailed information to people wanting to advertise to very specific kinds of people. Gone for decades now are the days of only being able to run ads on, say, bus shelters and hoping the right kind of people see it and buy your product or service. For some time now, companies have instead been able to approach a juggernaut like Facebook and say something like, ‘I want to advertise to just straight, physically active women between 19 and 45 in the mid-western U.S., who are upper middle class, take at least one vacation per year, have no kids, are some flavour of Christian, and spend more than 4 hours a day on their phones’ and Facebook would be able to get those ads exclusively to people who fit those criteria.

For a price, of course.

Nay, for that kind of granular targeting? For a premium.

That example above isn’t overstating it. People don’t seem to grasp the huge volumes of data they’re willingly offering up to companies like Facebook. Not just from their posts — though information found there is of course open for data mining as well — but from the connections you make, and from the detailed information that can be collected about where you go when. You may recall, or perhaps hadn’t heard, that Facebook was sued some years back and forced to change the functionality of their phone apps, because it was collecting data on its users (where they went, everything they did on their phones) even when the users weren’t on actively on the Facebook app.

Facebook is just one company doing this, of course. Consider Instagram (owned by Facebook) doing the same thing. And Twitter doing the same thing. And Tik Tok doing the same thing. And your internet service provider doing the same thing. The list goes on.

And Google? Well, that’s a whole other level of data collection. That isn’t just what you do and say and can be interpreted and extrapolated from your using an app, but everything done with Android phones (Google’s brand) as a whole is collected and packaged and sold to advertising companies. Time was, Google was just an exceptional search engine that made some money by advertising as well. These days close to 90% of Google’s enormous revenue, dwarfing Facebook’s income, is from advertising. From giving access to the mountain of collected data about you and all their other users to anyone who wants to pay them for it.

And don’t misunderstand the firehose of data it collects on those users. This isn’t tinfoil hat conjecture, but verified again and again: Google knows when you get up and go to sleep and where in the house your bedroom is (and, by proximity to other Google phones, with whom you sleep*), where your kitchen is and bathrooms are based on when you go there when, where you live (and so by extension what your income range is), where you work and on what floor (thanks to the altimeter in phones tracking stairs taken) and so what your job may be (more income range estimation), what department in the company your physical placement likely puts you in, who you interact with when at that job, then of course where you go in your free time and what that says about you — where you shop and what sections of those stores you spend the most time in, where you go to church, what bars you frequent in what areas of town (and what all that says about you, everything from food choices to political leanings to sexuality)… the list of nuanced information collected goes on. And on. And on.

Give some critical, deep thought to everywhere you go every micro-second of the day that you take your phone with you and the picture that those data points may be combined to paint about you, particularly when correlated to other data points about you and everyone else you’re around. And then realize with 100% certainty that that information is being sold to anyone who pays enough for it.

Or, I should add, not just anyone who wants to pay for it but who’s technically savvy enough to get at least concerningly detailed chunks of that information for free.

I attended a recent talk on digital privacy and security where the speaker had spoken with a teenager who had taken some time to validate a proof of concept that the youth had: The teen was able to find publicly available phone location history of one of his friends. He could literally determine where his friend lived, where he’d been when (friends’ houses, shopping, pharmacies, school, etc.) for the previous few months, and then make a map and detailed breakdown of it all.

I believe the teen in question had to have his friend’s phone number to be able to find all that info. It wasn’t just some random person he could do all this for. But a phone number of course isn’t a huge ask for even coworkers and business associates, let alone friends and romantic partners. Consider as well that after proving this could be done just for kicks, the teen was approached by other students who wanted to see this same mapping done for themselves. Now imagine: What if one of his friends asked him to do that level of tracking for, say, a girl the friend was interested in?

I’m not telling you how you should react to all of the above, but it creeps me out. And as the dad of a tween daughter, it’s very concerning that a kid with enough technical knowhow and a phone number for a person of interest can do this with information available to everyone everywhere who knows where to look for it.

Think of stalkers. Jealous ex’s. Think of abusive partners who want to know exactly when their partners were where and for how long. There’s a reason shelters try early to get new phones for the people they’re helping.

This isn’t to dump on a few key companies doing all this data mining. Yes, Google does it probably more than anyone else on the planet. But Apple collects huge volumes of data from their devices and apps, too. A big difference there being Apple (at least largely) keeps their data to themselves and don’t sell access to it to anyone who wants to pay for it, hence their touting of themselves as a privacy-oriented tech company. Which is at least better than other companies do. But still doesn’t go far enough.

Dark grey ethics of this highly detailed data collection aside, there are huge legal loopholes that have allowed companies to tap into this gargantuan information resource and make fortunes from it. Which is why our laws needs to catch up to the technology and finally help protect people who aren’t savvy enough (or interested enough) in reading the hugely verbose end user agreements on the likes of Facebook and Twitter to protect themselves. The E.U. is very progressive about this kind of thing and is leading the world on putting protections in place for digital privacy laws. They’ve recently gone toe-to-toe with some of the largest data collection companies on the planet, demanding new chocking off of data collection, and/or extremely basic and straight-forward phrasing to be transparent about what the companies are collecting and for how long, and they have won, forcing some companies to change their approach to interacting with users.

It’s a start, at least.

The best way to protect our data is to never have it collected in the first place. There are data breaches at big companies (and not to be outdone, at government level agencies) all the time, which give bad actors access to millions — sometimes billions — of elements of what can be very personal data about everyday people whose information was recorded and kept by, or in the case of some government agencies bought by, those organizations. That of course can’t happen if the data isn’t collected in the first place.

But we’re not there yet. Not by a long shot.

Given that these companies (and governments) are not yet being curbed enough from collecting as much as they can as often as they can and holding that data indefinitely, the best thing the public can do for starters is to control it better from themselves. Be more wary about who you give what data to when, ask questions about the data security and retention of companies asking for anything from you for a purchase (providing an email address or phone number for something like buying a book in a store should probably strike you as being unusually invasive), and, to bring it back full circle, make informed choices about what social media — if any — you choose to use.

Until the laws catch up to assert less, or hopefully no, data collection being allowable, you’re your own first and best defender of that information. Be informed and stay vigilant.

*Or, of course, don’t sleep but with whom you engage in, shall we say, more physical activity. There was an article not long ago about a wife who caught her husband cheating on her entirely because he was wearing his Fitbit (the health monitor watch-sized device people strap to their wrists) while having sex with another woman. His Fitbit had been set to alert the wife in case of medical emergency, and she was alerted to his heart racing… mid-coitus.

Fitbit was recently purchased by Google.